A Guide to Resonator Guitars

Understanding How Different Types Yield Different Tones

Katie here …. I’m very grateful to Koyl for writing this post. Thanks to his clarity, I feel more confident that I — who do not speak guitar! — finally understand not only the differences among the various types of resonators but also how each generates difference tonal qualities. Koyl is an accomplished guitarist and creator of ethereal sounds: Check out his recently-released album, Those Bridges You Can Only Cross on Your Own (available on Bandcamp). Koyl is also the author of a Substack, Aetherphonic, in which he discusses how and why he creates the music he does. In addition to creating ambient music and being an all-around great guy, Koyl is also an avid Whitley fan and long-time member of the ATCW Facebook group. I hope you enjoy — and learn from — Koyl’s post as much as I did.

Hi everyone,

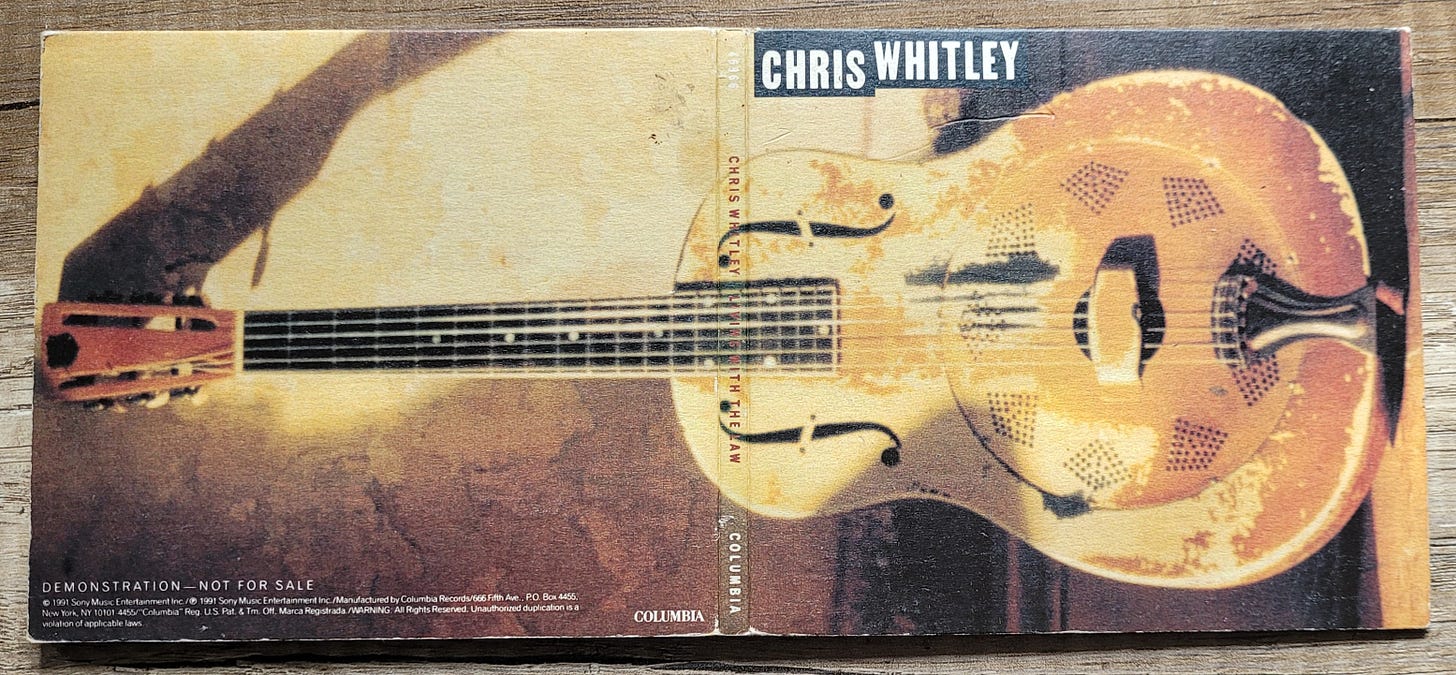

I’m Koyl, French musician and producer, fan of resonator guitars and of Chris Whitley’s music. I had to mention both in the same sentence because my fascination with resonators started the day I found a “Demonstration - Not for sale” digi-pack version of Living with the Law in a secondhand record store.

I don’t really remember how much I had heard of Chris’s music before this moment, but I was immediately drawn to what I was seeing on this cover. I brought the CD home, put it in my CD player, pressed play and as soon as I heard the few notes of the 1st track “Excerpt”, it felt like home… but I wasn’t prepared for what was about to come in the following tracks: this mix of raw energy and sound coming from both Chris’ guitar and voice with the wide and lush instrumentation coming from the band. In a strangely familiar way, it sounded like walking alone in a desert that I had never visited… maybe because it was speaking to the way 20-something years old me was feeling in the world….

… Followed hours of listening to the music while staring at the picture of Chris’ battered guitar, with my imagination drifting and trying to guess the backstory of every paint chip.

It was probably the mid-90s and resonator guitars were not easy to come by, and very expensive if you ever had the chance to find one… So my “crush” for resonators remained just that for a long time: a crush.

I spent the next two decades learning music production & mixing my post-rock and grunge early influences with electronic music such as trip-hop, dub, industrial, etc. My fascination for resonators and love for Chris’ music remained.

In 2015, I finally purchased my first resonator and started to record cinematic improvised soundscapes performed using this guitar, effect pedals and looper devices, something I was already doing with electric guitars. The music merged traditional sounds coming from blues, country or eastern influences with an ambient and experimental approach. I released those tracks in 2016 and consider this record to be my first really personal record, probably because, for the first time, I was able to combine the timeless spirit of music with my thirst to experiment and push boundaries. It’s like I had just fulfilled the prophecy I’d heard in Living With The Law.

After this record, I focused on production and electronic music until health issues and a burnout stopped me in my tracks a couple of years ago. This forced me to ask myself what I really wanted to do: What creative endeavors were actually nourishing and fulfilling to me?

And I naturally went back to resonator guitars…. Soon enough I was using them in unconventional contexts, magnifying their magic with effect processing, extended techniques, in genres they are not commonly found. All this to say that I love resonator guitars and I play them, but I’m certainly not an expert of their history, and even less a purist.

What follows is an attempt to make a practical 101 guide to resonator guitars that can be understood by everybody. I aim to give you a general idea of what they essentially are and to share enough information so you are able to better understand why and how they are different from your standard acoustic guitar and to distinguish among the different types of resonators. And because speaking about music is like dancing about architecture, I’ve included a lot of pictures and videos so you see and hear what I’m talking about.

What is a Resonator Guitar ?

The story of resonator guitars began in 1925 when steel guitar player & Vaudeville artist George Beauchamp asked John Dopyera to make him a guitar loud enough to be heard among the horns, reeds and percussion of the ever-louder bands of the era.

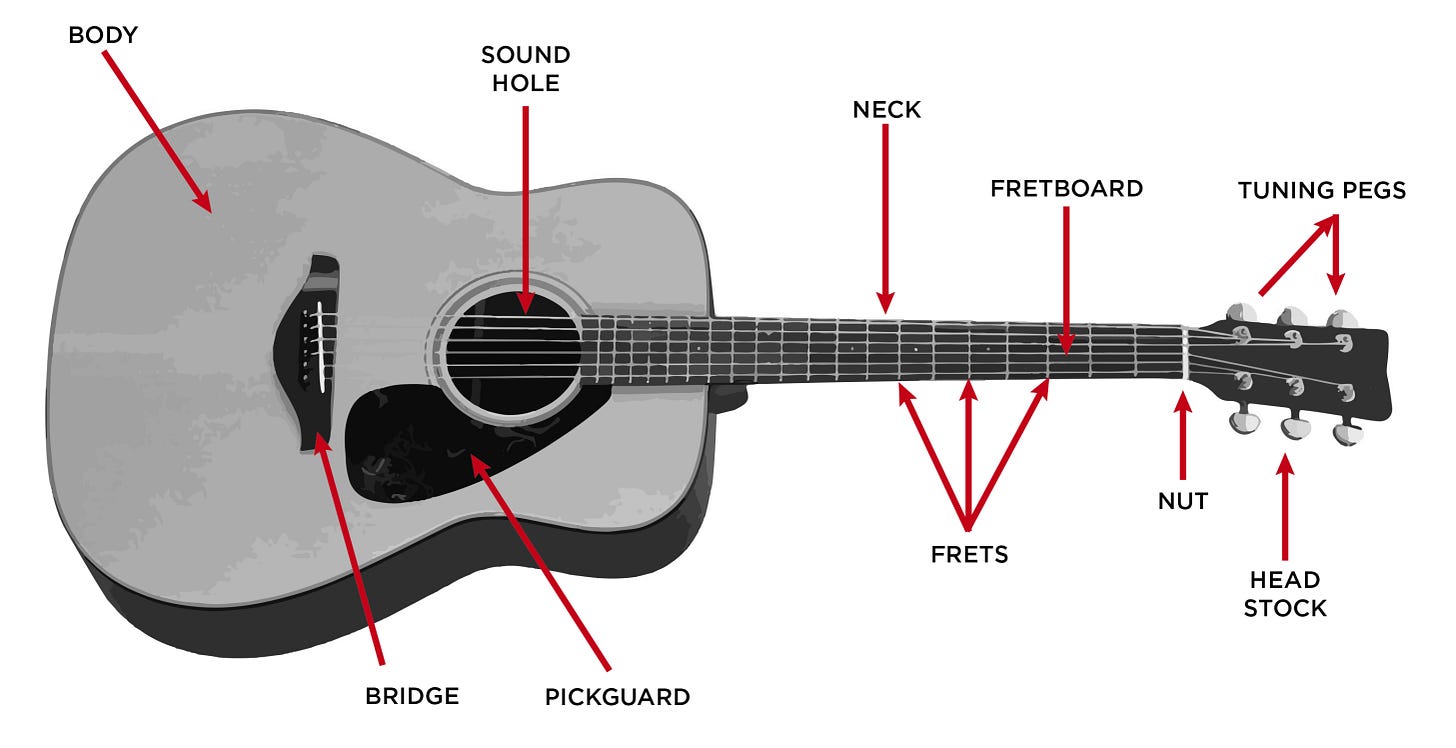

On a traditional acoustic guitar, the strings’ vibrations are transmitted to the surface of the body through the bridge (aka the part where they sit on the body side of the guitar. The part where they sit on the other end of the strings, at the top of the neck, being called the “nut”), it moves the air inside the body and creates the sound that goes out through the sound-hole that is cleverly placed toward the audience.

On a resonator guitar, the sound produced by the strings is picked up and amplified by specially “spun” metal cones (also called “resonators”) placed inside the body. You can think of a resonator guitar as an acoustic guitar with one or several loudspeakers that amplify the sound and diffuse it inside and outside of the body.

As we’re about to see, Dopyera experimented with several configurations and came up with a total of three successful designs that still are, to this day, the only designs you can find in resonator guitars. Each of these resonator types has its own tonal and mechanical characteristics, which tend to lend to a particular usage.

Some Lexical Considerations

The vocabulary used to speak about resonator guitars can be rather confusing: The same word can be used to describe several different things with its actual meaning depending on the context.

“Resonator”

The word resonator can be used to speak of the whole guitar, as opposed to other types of guitar. But the term “resonator” is also used to speak about the loudspeaker system that’s inside the body. Similarly to using a basketball to play basketball, you can play a resonator fitted with different types of resonators … context is essential to understand the actual meaning of the word. If someone says “I have a problem with my resonator”, more context is needed because you can’t tell if he’s talking about the loudspeaker system or the whole guitar (the issue could come from the neck or any other part other than the resonator).

As we’re about to see, a resonator (loudspeaker system) consists of one or several aluminum cone(s) and a specific type of bridge, but when we speak of a biscuit bridge or a spider bridge, we are talking about the whole loudspeaker system type.

“Dobro”

Another word often used instead of “resonator guitar” to characterize such guitars is dobro. Dobro was originally the name of the company created by John Dopyera and his brother (DOpyear BROthers) after he parted with National, the company he previously formed with George Beauchamp to produce the first models of resonators.

On top of being a brand and company name, Dobro is also used to name a very specific model of resonator guitar, made with a specific combination of parts: The “square-neck spider-bridge resonator” typically heard in bluegrass music that is meant to be played on your lap with a slide bar. It is so specific that it’s played in tunings that put so much tension on the strings that they would damage the neck of round-neck guitars and crush the other type of cones!

In this case, the term dobro means this very kind of instrument, meant to be played in a particular style and mostly in bluegrass and country music. Those who play in this way, with these tunings, on this type of resonator guitars describe themselves as dobro players, which implies they are not playing the other types of resonator guitars, nor a round-neck upright guitar, nor what is called “slack key” tunings (as opposed to the high-tension tunings I just mentioned).

Also, because of the popularity of the brand and I guess the easy pronunciation of the name, general usage has made it acceptable to use the term dobro to talk about all and any resonator guitar types, adding to the confusion. So the term dobro can mean the brand, the specific type of resonator instrument that goes with a specific playing technique, or just any resonator guitar.

Don’t stress too much about it though because, now that you know that the term can be confusing, you can ask for precision: The brand? The bluegrass instrument? Or just a resonator guitar? By doing so, you’ll already pass for a connoisseur! ;)

“Steel Guitar”

A steel guitar is a guitar meant to be played horizontally, using a slide bar to change the pitch of the notes. The two types of steel guitars are the pedal steel, which has pedals that change the strings’ tuning underneath the stand where the strings sit, and the lap steel, which is similar to a regular guitar but is meant to sit on the lap of the player.

Many people also use the term steel guitar to describe any guitar with a steel body, so if you happen to play a steel body resonator lap style, you’d be right to think you’re a steel steel guitar player. But it’s not something you’ll hear as it’s preferred to talk about playing a resonator lap-style or a dobro if it corresponds to your playing style.

The Three Types of Resonator Constructions

The Single-Cone Biscuit Bridge

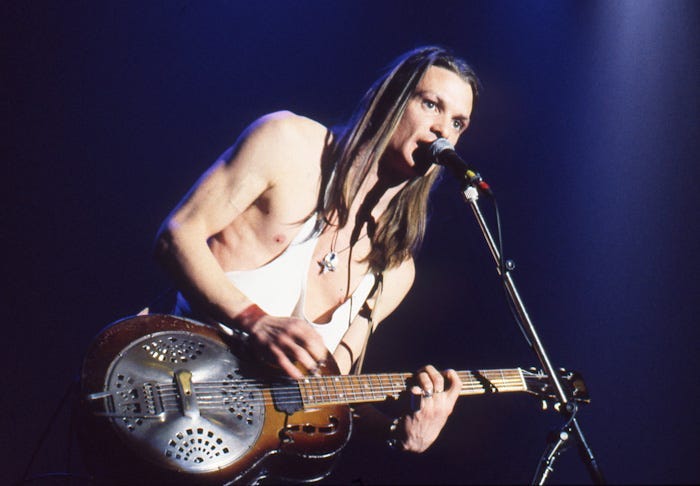

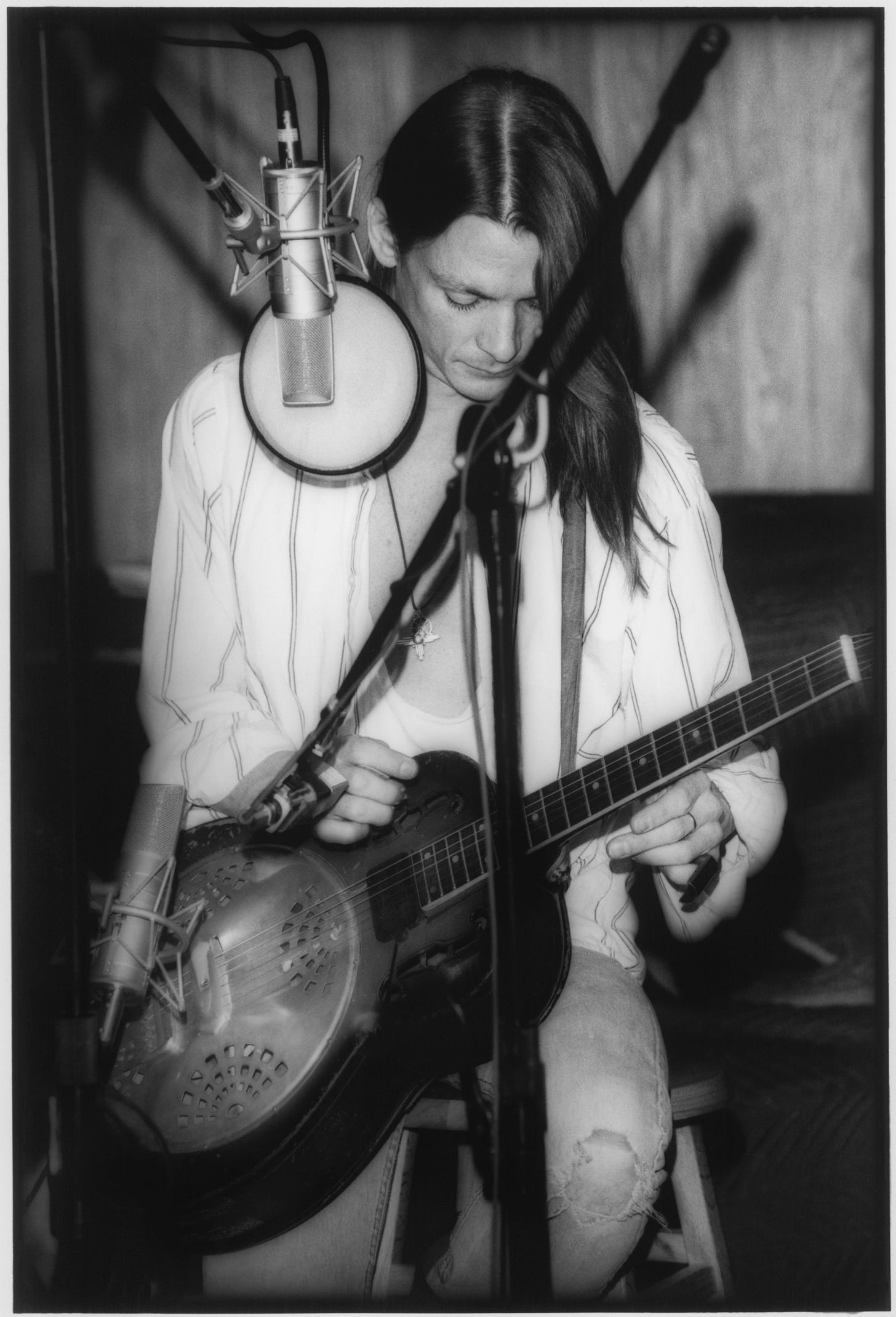

Let’s begin with this one since it is the simplest construction, and the one Chris is known for: His “Mustard” guitar is a biscuit resonator. A biscuit resonator uses a single 12”-cone mounted with a small wood disc that hosts a thin rectangle-shaped saddle to support the strings. The cone rests on a small ridge on the bottom of a well built into the body.

Because there is only one cone and the string vibration drives a single point on the cone, these resonators tend to generate a stronger fundamental tone with less complexity or overtones. An important factor responsible for the specific tone produced by a biscuit bridge construction is that the open side of the cone faces the back of the guitar, it is not pointed toward the audience, which means the sound reaches the outside in an indirect way. This construction makes for a punchy, assertive, loud and mid-heavy tone. Because the strings apply pressure directly on the cone, biscuit resonators tend to produce notes that have a sharp attack and a short decay (or sustain): Overall, the sound is quite focused, percussive and raw.

The biscuit resonator is commonly used in blues music, as illustrated in the video here and in the audio segment below:

The Tri-Cone

A tri-cone resonator is made of three 6-inch cones joined by a T-shaped aluminum bridge that supports a wood saddle. The use of three smaller cones and the strings’ not sitting directly on the cones creates a warmer, more complex and refined tone. The attack of the notes is softer and their volume decay is less rapid and more steady. Overall, the sound is very balanced and, in some ways, closer to an acoustic guitar compared to the other resonator types.

Tri-Cones, especially played lap-style, were a staple in Hawaiian music, which was all the rage in the 30s. They became a favorite of some blues player as well. Below is an excerpt of a video demonstrating the lap-style and illustrating the Hawaiian tri-cone sound:

The audio segment below (captured and excerpted from this video) is an example of how blues slide guitar sounds on a tri-cone:

The Single-Cone Spider Bridge

Created to try to emulate the tri-cone after John Dopyera left the National Guitar Company, because he wasn’t allowed to use the patented design, the spider bridge consists of a single 12”-cone facing the front of the guitar (and the audience). On top of and in contact with the cone sits a spider-web shaped aluminum bridge hosting a wooden saddle at its center. It basically takes the bridge principle of the tri-cone and mixes it with the biscuit bridge cone but backward.

The result is a sound that is more open than the biscuit and less full and sweet than the tri-cone. It’s a brighter and thinner sound that is often described as nasal and haunting. You might think of it as an acoustic guitar with some genes from a banjo.

Spider-bridge resonators are heavily used in bluegrass and country music, where they are mostly played lap-style.

Of course, you can play any music genre on a spider-cone.

To hear/feel the differences in sound produced by each of these three resonators, listen to these audio samples back-to-back:

Single-cone biscuit:

Tri-cone:

Single-cone spider:

Other Parts of a Resonator Guitar

Even though the type of resonator design used is the main contributing factor, the many other parts that constitute the instrument all influence the tone of a resophonic guitar (another term used to refer to resonators):

Different material can be used for the bodies, which also come in different sizes and shapes.

Vents or sound-holes come in many forms as well, same for the coverplates that are used to protect the cone.

Guitars made to be played upright or lap-style have a different neck suited to their respective playing style.

Body Types

Bodies can be made of metal or wood. If metal, they can be made of steel, brass or German silver — a copper alloy that usually contains copper, nickel, and zinc … but no silver at all! Steel tends to sound very raw, direct and sometimes harsh. Brass is ... well, brassier: warmer, fuller sounding, with harmonics that are more agreeable to the ear. I’ve never heard a German silver guitar, but I have a slide made out of it and I’d say it sounds like a cleaner, classier version of brass. It’s also what owners of such guitars tend to say online.

Wood is — as you might expect — woodier and more mellow. Of course, the tone changes depending on the type of wood used, but a wood body surely dampens the treble and harmonics of the resonator compared to a metal body. Common choices for wood-body resonators are maple, mahogany and spruce, solid wood or plywood, plywood being used in the cheaper instruments. There’s an ongoing debate about whether plain wood sounds better than plywood, given that, in a resonator guitar, the most important factor to the tone is the type and quality of the resonator.

Here is a video that compares three guitars, all-fitted with a spider-cone resonator, one with a brass body and two wood-bodied of different quality levels.

Body Size

Body size can vary as well: There are 12-fret or 14-fret bodies, named accordingly to where the body ends on the neck. A 14-fret body is smaller than a 12-fret and tends to sound “boxier” (less low frequencies, more mediums), and accessing the higher register of the neck is easier.

One is not necessarily better than the other, it’s all a matter of taste.

Two Types of Necks

A resonator guitar can employ one of two types of necks, depending on what playing style the guitar will be used for.

Guitars meant to be played upright (aka Spanish guitar) feature a neck with a rounded back so you can wrap your hand around it. On such guitars, the pitch of the notes is created by the contact between the strings and the frets.

Guitars meant to be played in a horizontal position on your lap using a slide bar (aka lap-slide guitar or lap-steel guitars) have a squared neck on which the strings are set very high above the fretboard. On these guitars, the pitch of the notes is created by the contact between the strings and the slide bar. Actual frets or fret markings are present solely to help the player know where the notes are; they don’t have a role in producing the notes as they do for upright guitars.

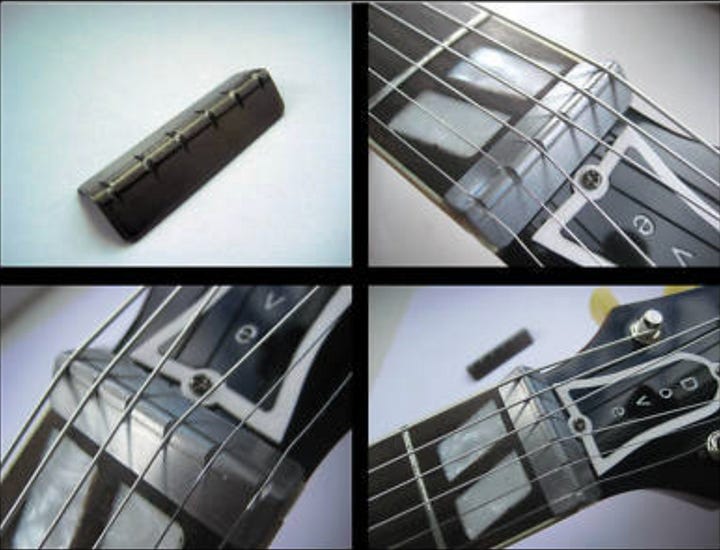

Square-neck guitars are less common and usually more expensive, but it’s possible to raise the strings of a round neck guitar with a device called a “nut extension riser” placed in-between the original nut and the strings so that you can play it lap-style, pretty much like a square-neck guitar. This modification is reversible, so it’s a good solution for players who want to give lap-style playing a try.

Coverplate

One of the most distinctive parts on a resonator guitar is probably the coverplate. The coverplate has two purposes: to protect the cone while allowing access to it if needed (coverplates can be unscrewed and removed) and to make the guitar look badass. Each type of cone comes with a specific type of coverplate. Knowing how to tell them apart comes in handy when trying to guess what type of resonator you’re looking at.

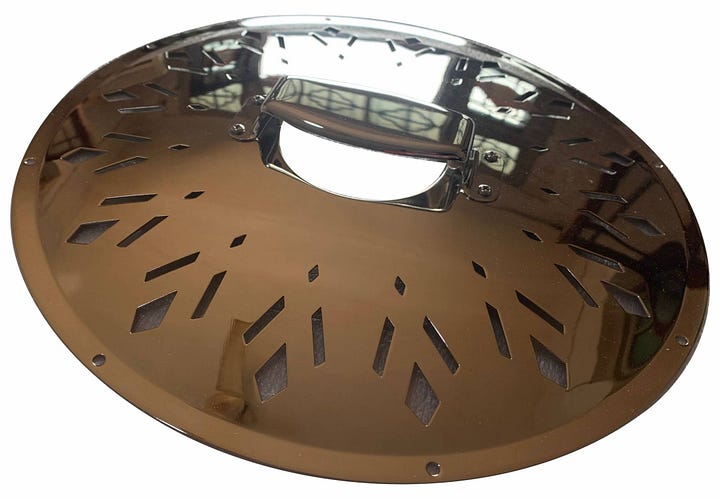

Biscuits resonators come with a round bell-shaped coverplate that usually sports diamond chicken-foot vents. A hand rest is screwed at the center to protect the bridge and allow access to it.

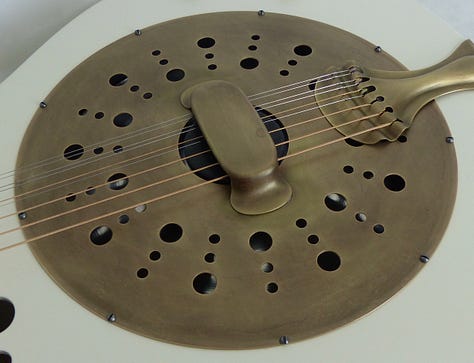

Spider resonators come with a round bell-shaped coverplate that is recessed at the center to accommodate the spider’s lower bridge compared to the biscuit’s. A hand rest is also present at the center. Most have large square holes arranged in this specific way.

Tri-cones feature a large, flat triangle-shaped cover with a T-shaped part that protects the T-bridge that connects the three cones. They also have large geometric cuts filled with thin grill cloth.

Builders can be very creative with coverplates: it’s a good way to give your resonator an original look, or even turn it into a real work of art!

Vents/Sound-holes

Vents traditionally come in F or round shapes, when they are not grill-shaped as is typically the case for tri-cones.

More unusual ones can be found on modern designs. It’s hard to quantify their influence on tone and volume, but I guess their role is to fine-tune or compensate the characteristics of the rest of the guitar, which would explain why some types of vents are often associated with a particular type of resonator and body material.

The Classic Resonator Guitars

The original resonators were made in a pre-industrial era and a lot of experimentation took place. Availability of parts came and went, so design decisions were probably very practical ones, based on what was readily available and/or the easiest to work with. Some resonators from the 30s have since became classics; some others were only made for a short time. In this next section, I will mainly discuss the different classic designs and the typical associations of parts and cone types.

Typical Tri-Cone Resonator Models

A typical tri-cone has a German Silver or Brass body, a triangle-shaped coverplate with grill-clothes and a T structure to protect the T-bridge that’s underneath. The top of the large-size 12-fret body has those larger grill-shaped vents that were originally only found on this resonator type.

Round-neck tri-cones are probably the most common, but square-necks are also very popular: they were actually the first resonator guitars ever made, and their rich, complex tone with lots of sustain make them very appreciated by slide players, especially in Hawaiian music.

Vintage and high-end square-neck tri-cones have one peculiarity that makes them even more special and magical for slide playing: The neck and body back are formed from a single metal sheet. Instead of being a piece of wood attached to the steel body, the neck is actually hollow and forms a single entity with the body! All of this adds to the sustain and haunting quality of the sound.

Typical Spider-Bridge Models

The most common combination for spider-bridge resonators is a wooden body, square-neck resonator played in bluegrass and country music. It comes with the typical spider coverplate and usually with grill-cloth equipped round sound holes.

Round-neck versions of the same combination are quite common too, and spider-bridge resonators are also designed with many other combinations of parts.

Spider-bridge dobros with steel bodies are much less common, maybe because the steel body already reinforces their nasal quality and it becomes too much for most players. But they do exist and have been produced. The Dobro M-15, commonly called “The Rose”, comes to mind.

Typical Biscuit Resonator Models

The biscuit bridge is the most common resonator design: easier and cheaper to produce, they come in all sorts of combinations. They also can be found in cigar box guitars, ukuleles, parlor-size guitars, and mandolins.

If we focus on standard-sized guitars, the most common combination consists of a steel or brass body, F-shaped vents, a coverplate with diamond or chicken-foot patterns and a round neck. They can utilize a 12-fret or 14-fret body.

Square-neck biscuit resonators are actually pretty rare! My personal solution is to put a nut riser on a round-neck.

A Bonus Maverick: The Fiddle-Edge Dobro

A fourth resonator design is worth mentioning here: the fiddle-edge Dobro, which was an attempt to produce a resonator guitar with a metal body that would be assembled without welding. Instead, the sheets of metal would be bent together at the edges, which gives the guitar a look reminiscent of a violin, hence the name. To cut costs even more, they made a body design that could be fitted with either a biscuit bridge cone or a spider bridge.

So you have a round-neck on a metal body with F- or round-hole vents, spider or UFO-style coverplate that can host a spider or a biscuit bridge.

I mostly encountered round-necks but square-necks were produced as well.

The fiddle-edge Dobro is a very unique instrument, that Chris actually owned and played.

This begs the question: Did Chris play his fiddle-edge with a spider bridge and cone, or did he swap that for a biscuit-style cone like on his other resonators? The following picture gives us a huge clue, if not an answer.

The bars of the spider bridge can be seen through the coverplate’s holes, so he apparently stuck with the Spider-style cone!

Sadly, the building process of the fiddle-edge Dobros turned out to be prone to a lot of mistakes and most of the attempts ended up being discarded, so they weren’t produced for very long. But when the build was successful, these guitars were amazing!

English blues guitarist and resonator player, Michael Messer, who is also a pioneer of importing good quality, eastern countries built resonators in Europe, has recently re-issued the fiddle-edge dobro.

You can hear all about this incredible endeavor in this two-part podcast (Watch here: Part 1 & Part 2). You will also learn a lot about the fiddle-edge Dobro in general.

Nowadays, high-end resonators are hand-made in small workshops or by single luthiers that can experiment with designs at the client’s or their own will. Cheaper instruments are crafted in eastern-countries by builders that produce a lot of different models for several western companies, which makes swapping parts and straying away from the classic designs easier. So please bear in mind that, beyond those typical combinations and classic models, everything is possible when it comes to combining parts.

For example, this is a guitar I used to own: Biscuit bridge and cone with a UFO coverplate on a brass-colored steel body sporting tri-cone like grill-shaped vents!

Having a wide array of models available despite the instrument being a niche product is amazing, but it can be daunting too, and you can’t always afford to judge the book by its cover. Mule Resonators comes to mind: a very reputable resonator builder that has made its specialty tri-cones that look exactly like classic biscuit models! (You’ll see examples in the following videos).

Before wrapping up, I’d like to share a couple of videos that talk about and let you hear the differences between the different types of resonators.

First one is by The Washboard Resonators, a channel that I highly recommend: After a few minutes of explanation, Martin plays different types and models side by side for a short time.

Another, shorter video from Martin, on which he plays the same short riffs on even more resonators:

Next is Benjamin Guillet, a very tasteful and talented player, who will introduce you to and then play four models. Among those are non-usual suspects, including the disguised-as-a-biscuit Mule Resonator tri-cone I mentioned above.

Another by Benjamin, with more models, on which he shows that resonators can be used for other styles than blues & country music:

I hope that this article was useful and that it gives you a greater understanding of and appreciation for resonator guitars. I think they are a perfect example of human creativity and collaboration. Resonators demonstrate that people of different horizons coming together can create something that reaches way beyond finding a solution to the problem they were trying to solve.

The fact that resonators are still being made and played, despite being technically irrelevant since the invention of the electric guitar in the 50s, and that their mechanics and physics are still a mystery a century after their creation is pretty incredible! It illustrates that there is more than the pure practical aspect of combining 0s and 1s to creativity … something that we could call “magic” maybe …. A magic that is pretty much impossible to convey with words or even recordings. You have to just be in the same room to hear their 3D sounds and play them to experience what they bring compared to standard guitars. But I hope, at minimum, you’ll get why some players are attached to, if not fascinated by, them.

They are not easy instruments to play, record or take care of, but they have a personality that’s different for each instrument. They can almost be considered a musician’s collaborator or friend: You don’t really use a resonator, instead you play with a resonator.

My guess is it’s the reason why Chris made them his primary instruments: They were his collaborators and he understood that the extra effort they require, or even the struggle they introduce, were part of his music and message, maybe mirroring his own struggle with understanding the world and how he fits in it, as any artist tries to. It’s hard living with the law indeed….

Koyl