Stories vary regarding how Chris came to meet Daniel Lanois, who was instrumental in getting Chris a recording contract and supported him during the recording process. Did they meet when Chris was playing a NYC gig at Mondo Cane? One Sunday morning when Chris joined a friend on a photo shoot in a NYC park? At a barbeque in New Orleans?

I didn't know the "real story" until I purchased some artist's proofs from photographer Karen Kuehn (she shot the 'Chris among the saints' iconic photo). It seems that Karen met Chris when he played a gig at the Exterminator Chili restaurant on Church Street in NYC. Instead of throwing cash in the tip jar, she gave him a note "good for one free photo shoot" and told her boyfriend Dan Lanois that he had to hear Chris. Chris eventually took her up on her offer, and they became good friends.

Invited to join Lanois in New Orleans, Chris said that he "cleaned his house and hung out with other musicians. But while Lanois was busy doing [other] albums, I met Malcolm Burn, a young producer who didn't intimidate me as much as Lanois." In another interview, Chris explained "I sort of didn’t want to ask Dan,” he says. “I felt like I’m not a collaborating sort, exactly. I figured I would be disagreeing with whoever I was working with on the production, and I didn’t want to subject our relationship to that. It didn’t seem like I should ask him, and he never really said anything about it.”

Living with the Law was recorded in Lanois' home studio (Kingsway) in a house that Chris said "influenced this record, all the people and the way they live there and stuff. The room there, it's a big room, and the way they record, it's not like a controlled environment. It's more like setting yourself to feel with the music." [LA Times, Aug 18, 1991] In fact, the recording was done late in the day, the studio often lit only by candlelight, as shown in this video:

An article in Rolling Stone (David Wild, Issue 612) captures the serendipity and excitement around Chris' discovery:

Lanois threw a huge bash at his house. One of the guests was a music-publishing executive named Kathleen Carey. "I asked him if he knew any great songwriters in New Orleans,'' says Carey, "and he told me about Chris.'' Carey was looking for a local songwriter to collaborate with another of her writers, but Whitley informed her that he really wasn't from New Orleans and also wasn't particularly interested in collaborating. He did, however, give her a tape of some of his songs, including rough versions of "Big Sky Country,'' "Poison Girl'' and "Phone Call From Leavenworth.''

When she got back to L.A., Carey … put Whitley's tape on in her car. She quickly pulled off the road and tried to get him on the phone. "The songs were incredibly real,'' Carey says. "They just hit me right in the gut.'' Within days she signed Whitley to a deal with her company, Reata Publishing. Carey's excitement proved contagious. Before long, labels were flying Whitley out to Los Angeles for meetings, and Carey had introduced him to Nick Wechsler, a high-powered manager … and movie producer…. Wechsler and his associate Danny Heaps loved what they heard and signed on to manage Whitley. A serious bidding war started to brew with nine labels interested in Whitley, but he quickly came to terms with Columbia.

A Brilliant Debut ...

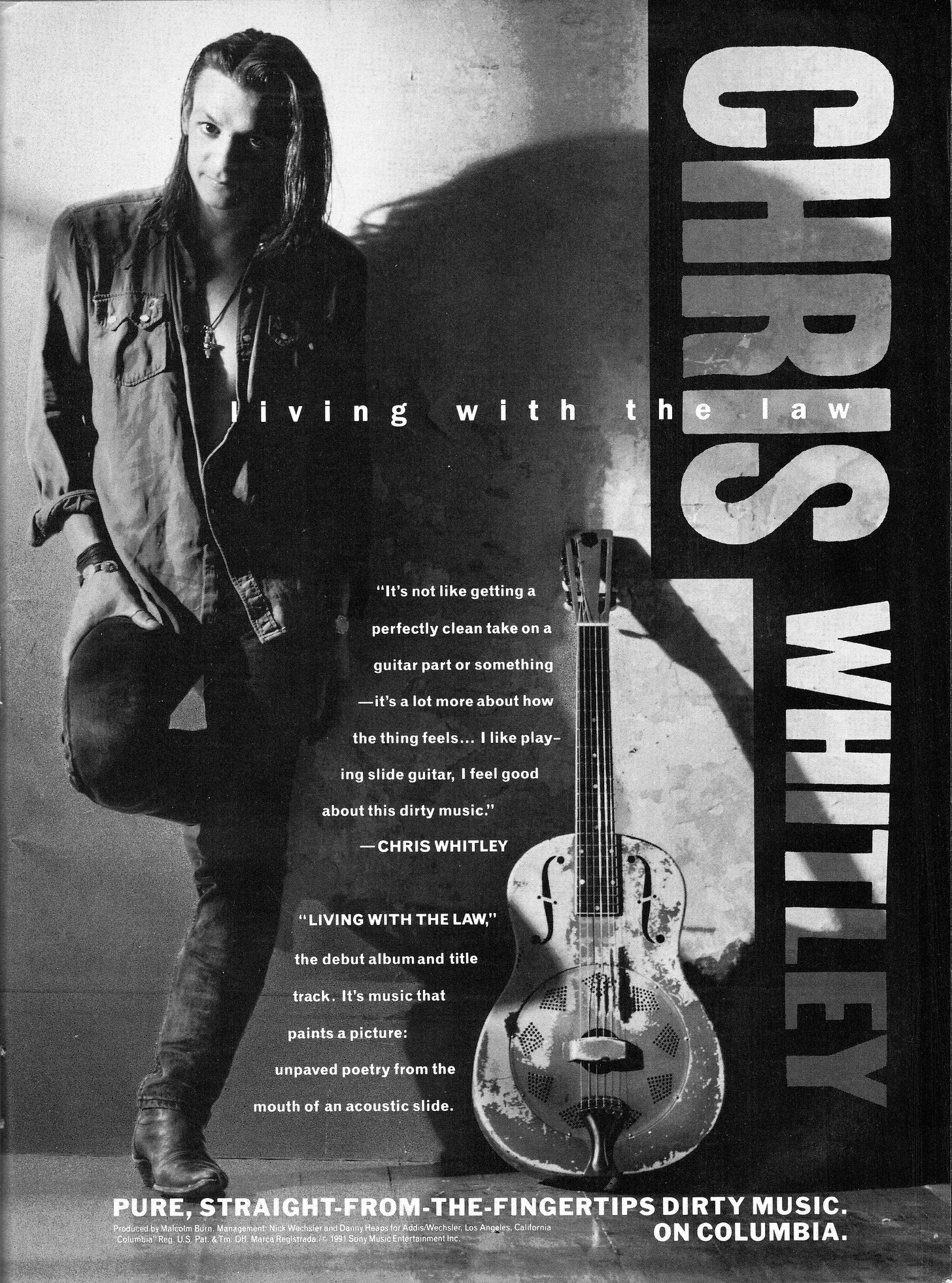

Few debut albums get the promotion Columbia Records (now Sony Music) provided for LWTL. As Graham Reid noted,

[T]he company sent out postcards to "tastemakers" and followed up a few days later with an advance promotional cassette mailout. Whitley undertook a promotional tour in June and sample 12 inches were sent to college radio. A full CD Digipak was sent to "taste-makers" on June 18 and the following day the promo CD ... was blitzed to AOR/ALT radio stations. .... Teaser ads were placed in various significant publications and after the album was eventually released on July 2 there were full-color ads in magazines such as Billboard, Spin, Musician, and Guitar.

The Dust Radio documentary captured the immensity of Columbia's push:

All that promotion certainly garnered a lot of interest, and the fact that the album was not only very good but also unique and timely guaranteed press interest. Time Magazine (August 12,1991) featured Chris among its "New Troubadours," singer/songwriters who create "highly personal rock 'n' roll" and whose songs "have passion, intimacy and a shared but singular voice." And the reviews? Uniformly laudatory!

Paul Evans, Rolling Stone (Issue 608/609): Chris Whitley's extraordinary debut album, is fantasy blues - bona fide poetry and National steel guitar conjuring dream imagery from some surreal western movie. Riveting and original, Whitley mines roots music not as an imitator but as a visionary who trades on archetypal symbols and classic riffs to fashion his own twilit American mythology. .... [T]here hasn't been music as wise as Whitley's in quite some time.

JT Griffith, All Music Guide: An exceptional and mesmerizing debut, one with the potential to inspire all who hear it. An album Robert Johnson may have recorded, were he still alive.

Tony Scherman, Musician (October 1991): What ultimately makes Living with the Law such an arresting debut are the songs, artfully drawn and insinuatingly tuneful, coming as close to short-story writing as anything that can be hummed. An utterly addictive album.

Steve Morse, Boston Globe (July 11,1991): Originality is rare today in any medium, so it's a double treat to run across this exquisite new album. .... [Whitley's] unusual bent-note singing and spare but deeply affecting lyrics mark him as a true discovery. Songs like "Living With the Law," "Big Sky Country" and "Phone Call from Leavenworth" linger long after the music ends.

... But Not to Chris's Liking?

As well-received as LWTL was, Chris didn't particularly like the album. "Hated" might be a bit of an exaggeration, but Chris strongly believed that the album's production - so widely praised by critics and so eagerly embraced by fans - didn't reflect his "sound." In an interview with the Times-Picayune, Chris said

"I just feel like I have made a record and I have toured for a year and I can look back on it and say, 'Why has some of this been dissatisfying? Why have I had to explain myself away so many times ... like what I was doing was not apparent at all?'"

"I think it has been appreciated for different reasons than I would have [it]. That's why a lot of the time, a lot of the praises it got, I couldn't completely say, 'Yeah, well, thanks, you know, that's great.'"

"I think it's very listenable and I like the way it sounds. It doesn't really sound like me, particularly, at least not completely. It has elements of where I'm at but it's not like the whole thing. I feel like the record is much more excruciating than it sounds, honestly."

In various interviews, Chris described the album as "precious," not "as gnarly as when I play them alone," "a little too pretty." He repeatedly noted that, except for "Big Sky Country," all the songs on LWTL were written to be played solo -- just Chris, his guitar, and his boot. "When I play the songs off 'Living' solo, they're me. I was working in a picture frame factory in Brooklyn. I didn't have a band, so they were written as solo works." [Philadelphia Inquirer, June 23,1995]

Here's a session musician and fellow guitarist (The Psychedelic Furs), Knox Chandler, describing the stark difference between Whitley solo vs. Whitley on LWTL (from Guitar Moderne YouTube channel):

Chris also rejected the singer/songwriter, Americana, rootsy pigeon-hole that he was stuck in. Singer/songwriter? "It's self-important. You can play something in a way that it gets corny. I combat that in myself a lot because I feel like I write romantically, which is always melodrama on a certain level." [Press of Atlantic City, August 7,1995] Rootsy? "I feel more -- I dunno -- acid-rock. .... I guess everyone needs a reference point ... I guess I do sound old-fashioned when compared with Paula Abdul." And the to-die-for Time article? "Man, to be honest, that Time thing bothers me. .... Fuck, that guy should have listened to the record." [Graham Reid, "CHRIS WHITLEY INTERVIEWED (1991): The Law man living with the lore," May 24, 2010 on Elsewhere]

… A Kiss of Death?

As contradictory as it may seem, I've concluded that Malcolm Burn's masterful, beautiful, and original production of LWTL both launched Chris's career and signed its death certificate. As Chris noted above, LWTL is beautiful, and it certainly got our attention; but, ultimately, it did not reflect "the sound" Chris wanted to make. You might say that LWTL made a false promise: It suggested that we could expect more of the same in future releases.

Not so! As much as I loved LWTL (actually wore out my first CD and had to repurchase), I was shocked and utterly repelled by Din of Ecstasy. Couldn't listen to more than a few seconds of each track before skipping to the next. Ultimately threw the CD in an odds-n-ends drawer, where it languished for years. When I purchased Live at Martyrs', I thought, "Gee, Chris must have written several new songs that I missed." Hearing "Narcotic Prayer," "WPL," "God Thing," and other Din songs performed acoustically, I loved them!

Many fans of LWTL had a similar reaction to Din. Donny Ienner, the Columbia/Sony chief who signed Chris on a 3-record contract, was especially dismayed. In the Dust Radio documentary, Ienner seems genuinely confused by Chris's musical trajectory and mourns the "dark turn" his lyrics, his sound, and his life took from Din on. Kathleen Carey - the music publisher who promoted a LWTL demo to Ienner - dittos those feelings. As I watched their interviews, I repeatedly thought: What's so cheerful about LWTL? A poison girl, Leavenworth prison? "Momma cry and Daddy moan/Starving in some trailer home/Want to burn it down"? "I do my dreaming with a gun"? Granted the sound paints beautiful pictures, but the lyrics certainly do not.

Thus, the conundrum, enigma, dilemma of Chris Whitley's musical career: to achieve recognition and commercial success, he had to not sound the way he was meant to sound. Would you have noticed LWTL if it had been presented with the same sparse production as Dirt Floor? Would you have ever even heard any of its songs? Not the kind of tunes that get a lot of play on most radio stations, right?

So. I am eternally grateful to Malcolm Burn for producing LWTL in a way that got Kathleen Carey's attention, Donnie Ienner's attention, the critics' attention, the DJs' attention, and, ultimately, my attention. Because I was so blown away by LWTL, I kept coming back to sample whatever Chris Whitley did and therein discovered the soundtrack to my life, that inexpressible something (Truth?) conveyed by his words and sounds. LWTL baptized me in the Church of Chris Whitley, touched me in a way that no other musician has ever matched. Over the years, my faith has been simplified and purified. Today, my favorite Chris Whitley? Anything "straight": just his voice, his guitar, and his boot. I guess you could call it "old-time religion."

Kiss of death? Cruelly true. The music business machine is cruel. Opportunity comes dressed in adulation, art praise, promises and lies. A producer needs the artist. Record companies need the artist. Two examples from the documentary Dust Radio. Ienner said that he hoped to get twenty years out of Whitley. That’s a sound investment for long term returns. Then the production. Burns said he finds it hard to listen to commercial music from back then. Yet LWTL is as slick as Nashville. Burns produced polished product.

I think it was inevitable he wouldn't stay in that mode for long because he was an actual artist and was stubborn about doing what people expected him to do. He chose to chase his own muse, sometimes to his detriment, but we got an amazing catalogue of music because he chose that rather than taking the easy way out and redoing LWTW a bunch of times like he could have.