Reiter In

A "Deathbed" Album?

Before plunging into a discussion of Reiter In and its individual tracks (coming in Part 2), I think it may be helpful to ‘set the stage’; understanding the context in which Whitley found himself in June 2005 may offer insights as to why he did what he did when he did it. It’s particularly important because so many fans and critics view Reiter In as Whitley’s “deathbed album.”

Deathbed Album

A deathbed album is one written and recorded at the end of a musician’s life. Albums commonly included in this genre include Warren Zevon’s The Wind, Joey Ramone’s Don’t Worry about Me, and Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker. Some musicians have released deathbed albums — and lived for decades! Neil Young’s Prairie Wind (released in 2005) was very much colored by his being diagnosed and treated for a brain aneurysm, but two decades later, he’s still very much alive and making music. Masta Ace’s Disposable Arts was written and recorded in 2000 as he was diagnosed and treated for multiple sclerosis, a disease he thought signaled the end of his music career — again, alive and kicking and making music decades later.1 If you know others in this genre, please name them in the comments.

Whitley died five months after Reiter In was recorded, and the album was released about five months after his death. Likely because of this timeline, many reviewers addressed Reiter In as a deathbed album:

Writing for All about Jazz, Doug Collette compared RI to The Wind: Chris Whitley died of cancer in November of 2005, a tragedy that robbed us of one of the most distinctive yet unheralded musicians of our time. Inspired and inspiring as Reiter In may be, this product of his last recording sessions is every bit the statement of closure and adieu that The Wind represented for the late Warren Zevon.

Steve Terrell titled his review “Deathbed Rock” and carried that perspective throughout his essay, beginning as follows:

Call it “deathbed rock”.

Warren Zevon is the master of it, having crafted his farewell album, The Wind, as he was dying of cancer. The album was released shortly before he died in late 2003. …. And now comes Chris Whitley …. Whitley, a Texas guitar slinger who died of cancer in November 2005, didn’t give up the ghost until after making one final recording with a group of friends he dubbed The Bastard Club.

Thom Jurek opened his review for All Music pondering, One has to wonder if Reiter In is, in fact, the late Chris Whitley's last will and testament in terms of recordings. Done in the first three days of June, 2005 — he was already ill — this set was recorded in New York with a host of friends he called "the Bastard Club".

A Stylus review opened by acknowledging Chris’ death and how it might affect what one expects Reiter In to sound like: Chris Whitley passed away, surrounded by family, on the 20th of November, 2005; Reiter In was recorded in June of the same year. As such, you might expect something spectral, music soaked with the thought of death.

So, yes, lots of gloom and doom and sorrow about Whitley’s passing. But is Reiter In appropriately classified as a deathbed album? Here are arguments for and against such a designation.

Arguments for ….

Recall that the previous years had been very productive and, I would guess, exhausting:

1998 - 2001: Dropped from Sony in 1997, picked himself up to record Dirt Floor and complete a 300-gig tour (March 1998 - April 1999); Live at Martyrs’ and extensive touring before and after; Perfect Day and, again, extensive touring while also writing, rehearsing, and recording songs for Rocket House; European tour followed by Rocket House tour, the latter interrupted/cancelled when he ‘lost it’ at the Portland gig in July — one of many times he would lose it during the last years of his life. Dropped from Dave Matthews’ ATO, the label on which RH was released. Picked himself up to do several dozen solo gigs between late-August and mid-November.

2002: Pigs Will Fly, another European tour, and then a quiet Fall (working on his next album?)

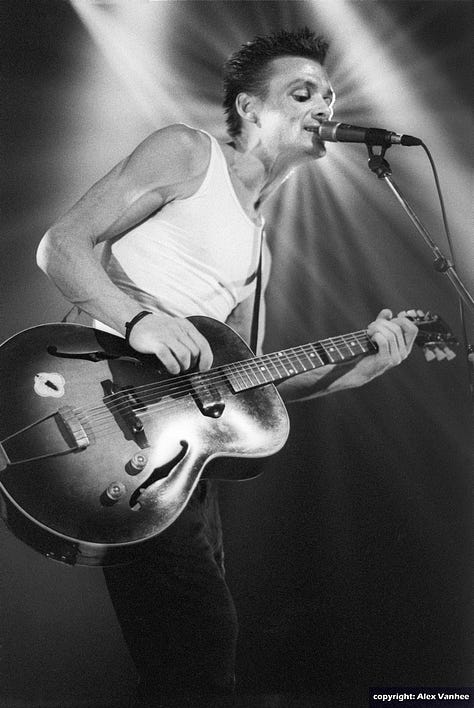

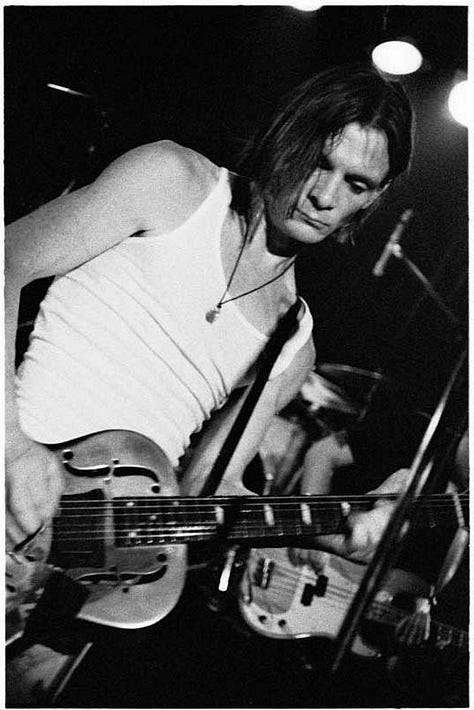

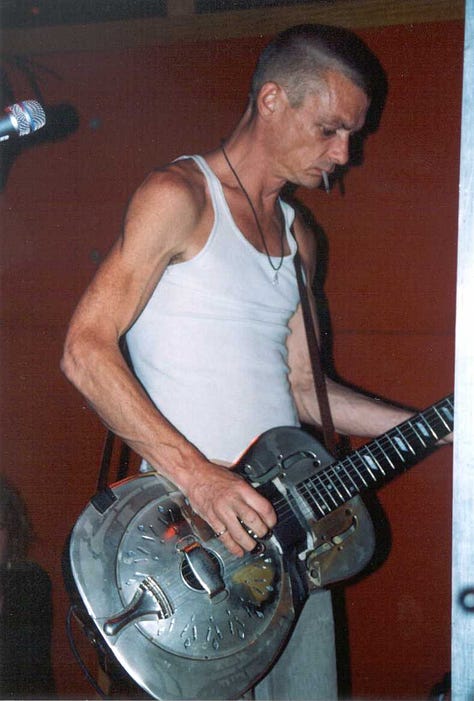

2003: Hotel Vast Horizon, a heavy HVH tour schedule in April and May, and Australia/Europe tour from August - October. By this time, Whitley’s physical decline was becoming evident; just look closely at his right upper arm and shoulder to gauge his loss of body mass.

2004: Weed and War Crime Blues plus writing/recording his next studio album, heavy touring in March and April and again through the Fall (some October and many November gigs cancelled), his mother’s death on October 4.

Spring 2005: Soft Dangerous Shores, short Australian tour and recording Dislocation Blues during March and April, Reiter In in early June.

By the time Whitley made his way to Old Soul Studios in early June 2005, he had recorded 10 albums in the span of just 7 years and had performed many 100’s of gigs all over the world. He’d experienced triumphs (e.g., the overwhelmingly positive, laudatory response to Dirt Floor) and defeats (e.g., being dropped by Sony and by ATO, episodes of alcohol abuse, romantic relationship issues). By late 2004, he was a shadow of himself — wasting away from the cancer he did not yet know afflicted him. The Classic Rock retrospective on Whitley’s life and career, “Fallen Angel: The Life and Death of Chris Whitley,” noted that

Both men [Jeff Lang and Malcolm Burn] saw first-hand how drink and his devils had ravaged Whitley. In Melbourne he went on a three-day bender before recording. He was calmer when Burn encountered him, but weaker too. “I knew something was up as soon I saw him,” says Burn. “He’d lost a ton of weight, and had these intense coughing fits where we’d have to take a break. Yet he was still just as devoted to his craft, if not more so.”2

His mother’s death had also affected him deeply; I conveyed some of this in an earlier post that drew heavily from Jeff Lang’s chapter in Some Memories Never Die in which Lang discussed his friendship with Chris and Chris’ harrowing breakdown in mid-October 2004, during their joint tour.

Consider this short passage from Lang’s book:

Chris’ mother had died only a short while before these shows, and he was devastated by her death. She was an artist, a sculptor, and he was telling me about how she couldn’t afford health insurance. He viewed her death as her being punished for being an artist and allowed to die because of how little value society places on art. [my emphasis]

Not a good frame of mind — especially given his own situation and how we now know his life would end months later. As recounted in the Classic Rock article,

In 2004 Whitley lost his mother, and her death hit him hard. Toughest of all was the fact of her dying alone and in poverty, her devotion to her art having brought her neither material comfort nor salvation. The parallels would have been obvious to him, and he threw himself into his music as if a hellhound was on his trail. [my emphasis]

The Classic Rock article further supports the deathbed album claim by describing Whitley’s circumstances:

In Spring 2005 Whitley was offered a US club tour. He took it, against the counselling of friends worried by his declining health and despite the small amount of money it would bring him. He had his reasons for going; his relationship with Buerger was floundering on the rocks of his boozing.

Back in New York Whitley cut what would be his final record, Reiter In, during a drunken three-day session and with a pick-up band [sic - NOT “a pick-up band” but friends and fellow musicians]. …. At the time of making it he was facing eviction from his apartment.

That article also quotes Whitley’s romantic partner, Susann Bürger, saying, “He had such a hard time making compromises and he paid the ultimate price for it. In German we have a saying that you can be tired of life. And at the end he was like that, tired of living.”

So, yes, Whitley was in dire straits during the first half of 2005: plagued by poor health, a poor bank account, and a troubled relationship and facing eviction from his NYC apartment. But was he contemplating his impending demise? Maybe, maybe not.

Arguments against ….

Given such a difficult several months, it’s no wonder Whitley wanted (needed?) to spend time with the Johnny Society gang (and others) with whom he and the Vast Combo had toured in Spring 2003: Fun with friends!

A music critic writing about Reiter In for Stylus Magazine presented what I believe to be a likely explanation of the context in which the album was recorded. S/he noted — right off the bat — that, when released, the album’s cover art portrayed “[a] figure, presumably Whitley, ascend[ing] a staircase in what looks like a subway station, walking towards an entry that pours forth light” — conveying the archetype of us mortals seeing/being pulled toward a bright light as our lives ebb to nothingness. The inside art — a ghostly photo of Whitley with the caption “The rider is the ghost that leads the body” — reinforces that archetype.

But we should understand that Whitley likely did not choose this artwork. It seems that the album was still being produced/mastered/manufactured through late 2005 and not released until late-March 2006. More likely, the album’s producer Kenny Siegal (and his fellow Bastard Club members?) chose artwork acknowledging that Reiter In would forever be known as Whitley’s posthumous album.

Question: Is a posthumous album automatically a deathbed album? The Stylus review says “Hell no!”:

But Reiter In isn't about death, it's about life, and it's not credited to both Whitley and the Bastard Club … by accident [The Bastards “would probably have become Whitley's first real backing band had he lived”]. It doesn't even feel like a wake, really; it's a very talented musician and his friends having fun. Any record that starts with loose, hammering covers of “I Wanna Be Your Dog” and “Bring It on Home” isn't going to be bogged down with self-conscious sentiment. There are more important things to do.

Furthermore, Whitley felt sick, but didn’t know that he felt sick because his body was ravaged by terminal lung cancer. He toured during Summer 2005, although several August gigs were cancelled due to poor health. But, as the Classic Rock article defines the Fall 2005 timeline, his diagnosis arrived months after Reiter In was recorded:

Whitley accepted an entreaty from his brother Dan to go and rest up at the ranch house of an old family friend in Houston. Once back in Texas3 he began experiencing chronic pains in his right leg. He’d had a long-standing aversion to doctors, but was persuaded to go for a check-up. He was subsequently diagnosed with terminal lung cancer.

I quoted Susann Bürger saying “In German we have a saying that you can be tired of life. And at the end he was like that, tired of living” [my emphasis]. But what does “at the end” refer to? I’m guessing that it refers to late-September/October 2005.

Also consider what we know about events between those few days at Old Soul Studios and Whitley’s cancer diagnosis. Within a week of leaving Old Soul, Whitley played the Roots on the River music festival in Bellows Falls, VT. He looked desiccated, but sang and played guitar fairly forcefully. An obituary in the local newspaper, The Brattleboro Reformer, recalled the festival, noting that Whitley’s 6-song set was uneven and that he staggered and spoke of his mother, who had died eight months earlier. (A festival employee was quoted as saying “He was reaching into dark, private spaces, suddenly bursting out with talk about his mother; it was like bloodletting onstage.”)

Not to be disrespectful, but GUI — gigging under the influence — had sometimes resulted in uneven Whitley performances, which occurred more frequently in the last year of his life. In any event, he was obviously still looking forward, as illustrated in this excerpt from the Brattleboro Reformer obit:

As the festival wore down last June, and the party began wrapping up, Ray Massucco (a volunteer with the festival) convinced Chris Whitley to hop into his grey Volvo sedan, and to let Massucco drive him home. "Chris said to me, 'Hey, you got a CD player in here?' Then he put his new album ['Soft Dangerous Shores' - not released until 6 weeks later] on full blast, and he started singing along." …. "Here is this guy who could barely talk, but he could sing -- it was amazing. It wound up being a very positive experience. We parted with the understanding that we would see each other in August [when Whitley was scheduled to play at The Windham in Bellows Falls]."

Also indicating “Hell no!” as to a posthumous album necessarily being a deathbed album is this: No one refers to Dislocation Blues as a deathbed album. Recorded just two months before Reiter In, Dislocation Blues wasn’t released until August 2006, almost five months after Reiter In. Further suggesting that Whitley didn’t think he was “knock-knock-knocking on heaven’s door” is Jeff Lang’s recounting Whitley’s ecstatic reaction to hearing the Dislocation Blues mixes:

He was a bit drunk, at his apartment in New York City, and we spoke for a few hours with the album blaring on repeat in the background. He loved how it had come up, had convinced himself that me and the band had played great but that he had been awful and was really relieved and pleased that this wasn't the case. It was the last time we spoke but he was happy, loved the record we'd made and we spoke about the possibility of doing more in the future. [my emphasis]

Looking back after Whitley’s death, some fans seem almost to perceive Soft Dangerous Shores as a deathbed album. Lyrics such as “Say once before you go/before I’m gone” (“Fireroad”) and “Too late to find a way/End game holiday” (“End Game Holiday”) seem to presage Whitley’s demise, but how far back must one look? To “Dirt Floor” and its “There’s a dirt floor underneath here/To receive us when changes fail”? Hindsight surely colors our perceptions.

Conclusion?

So, yes, Whitley was probably tired to the bone, but, as Nat King Cole — one of his favorite singers — sang in “Pick Yourself Up”,

Whitley kept moving forward, working “like a soul inspired” because music-making was his raison d'etre; his commitment to his music, to his chosen means of expressing himself, could not be denied. As one reviewer noted, “[Reiter In] sounds like a man playing as if his life depended on it - or perhaps living because his playing depended on it.” And, if Reiter In is “deathbed rock,” another reviewer, Steve Terrell, wrote that it stands as “a defiant middle finger in the face of smiling Sgt. Death” and “It’s just a strong album, indeed a tough album, that’s more about his life than his leaving.”

Most perceptively, for those who insist on viewing Reiter In as a deathbed album, this reviewer strikes just the right note:

To the end, [Reiter In] sounds mostly like people having fun, no grand statements made. As Whitley himself chuckles at the end of “I Go Evil,” “it's cornball but cool.”

And that wouldn't be so crucial if Reiter In wasn't a posthumous release, but it was and it is. The temptation to do something “important” as an artist if you know you're sick with lung cancer must be enormous, but Whitley didn't succumb and so this album does wind up being significant. It's a particular kind of courage, to continue to live and love and pay homage and even party in the face of death and passing, to acknowledge death but to be unrestrained by it, and Chris Whitley's refusal to turn this music into a sob story speaks volumes about the musician and man that he was. The music here is fine and spirited and would be another good entry into an astonishing body of work had Whitley lived; as it is, Reiter In is the finest effort he could have left us with, and a fitting celebration of his life and work. ~ Stylus

If you’re thinking I’m too old and un-hip to know Masta Ace, you’re right: I encountered him while searching for deathbed albums. See a reddit post here.

The way this is written seems to suggest that Burn produced Soft Dangerous Shores after Lang worked with Whitley on Dislocation Blues. Actually, SDS was recorded at Burn’s upstate New York home studio in the summer of 2004 whereas DB was recorded at a studio in Melbourne, Australia, in the spring of 2005.

We know that Whitley was back in Texas before September 18th because he appeared at a Houston benefit for a recently deceased member of Buddhacrush on that date. Furthermore, announcements from a week earlier about the benefit were already listing Whitley as attending.

I always loved Reiter In in particular because it sounded like Chris and some friends making music for the joy of it. It's raw, beautiful noise.

Personally I never attached a "deathbed" label to the record, since it seemed full of life to me. I think if Chris would have lived, we would have seen a lot more of this type of record from him, a kind of less "serious" approach, more collaboration, almost a more folk-type approach on recording music where its presented rough and raw, worts and all, instead of the highly produced and meticulously crafted records he'd made before.

Creating art at the high level he did, and trying to scratch a meager living was exhausting, as it would be for anyone, and I have the feeling that Chris just wanted some of the joy of making music back.

I guess I have never saw his final few releases as "deathbed" albums. Almost his entire catalog is filled with (a long with a TON of songs, all, in my opinion, about the same woman) songs about death and the in-between. I think he was just born an old soul, a description many people seem to agree with.