Chris Whitley: Right-Hand Man

Chris Whitley’s right hand style was entirely unique, and integral to the texture and power behind his sound.

Note: I am delighted to host this guest post from Jason Wiegand (aka Lee Roy), whose insightful comment and vivid description I quoted in an earlier post on Chris Whitley’s guitar playing. Jason is an inaugural member of the All Things Chris Whitley group on Facebook, and he knows whereof he writes! He’s been studying Chris’s guitar techniques for more than a decade and has played resonator guitars in a “just for fun” band, Hiram Rapids Stumblers, for about that long. Check out his band on Facebook and YouTube.

Chris Whitley, as we all can agree, was a singular guitar player. Entire books could be written on his equipment, tunings, and chord choices, his use of noise and dissonance and his inimitable style. It’s been twenty years since he passed, but many of us are still enthralled and unraveling the knots in the big ball of string he left us as a guitar player.

It's normal for folks to focus on a player’s left hand, or fretting hand, and to assume that there is where the magic happens … and Chris had plenty of magic on the fretboard … but, in my opinion, discussion of guitar players often neglects the right hand, the rhythm hand, the side of the guitar that is actually producing the sound we hear, the notes we feel, the rhythm we dance or stomp or clap to, the dynamics in volume that produce the tension in music to excite us.

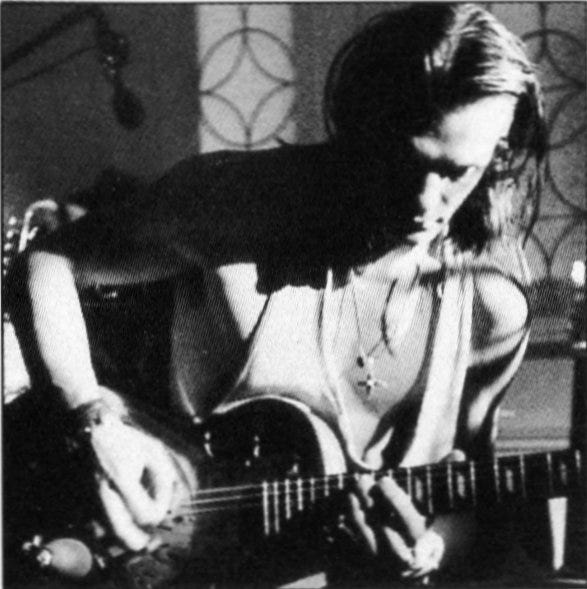

“The hands - God, yeah. There's a photo in the Living with the Law booklet where he's hunched over the National, his face half in shadow, those huge meat hooks of his just dominating the composition. Hands like a strangler.”1

Chris Whitley’s right hand style was entirely unique, and integral to the texture and power behind his sound. Following here, I’ll take a stab at explaining what I’ve gleaned from him over the years as a guy who has spent a little over two decades attempting to adapt much of Chris’s unique picking style into my own playing, and to do my best to not get too technical for any of you folks who don’t play guitars.

First of all, Chris was a weird player. I don’t mean that as a pejorative, but it’s the only word that fits. He did stuff wrong, in the sense that no guitar teacher would ever tell you to tape on some fingerpicks, grab a heavy flatpick, then tear at and smash your guitar like it owes you money … but thankfully Chris didn’t constrain himself with what a guitar teacher would say or what others would view as the “correct” way to express himself on a guitar. Chris was not a delicate player, even in his most delicate of songs. He played the hell out of his instruments, and that singular, aggressive attack defined his sound as much as any amp, guitar, effects pedal or tuning we could discuss.

A Hybrid Picker

Chris’s mode of picking, called “hybrid picking,” involves a standard pick (although Chris, of course, modified his) held between first finger and thumb, and two metal fingerpicks on his middle and ring fingers. This in itself isn’t an unusual method. Roger McGuinn of the Byrds, Robbie Robertson of the Band, even Steven Van Zandt from the E Street Band all used this arrangement of picks. Of course, none of them sound anything like Chris!

For you non-guitarists out there, try this: Pinch your pointer finger and thumb together and pretend you’re holding a guitar pick. Play a little air guitar with it, no one is watching. You can strum up, strum down, pick a single string with rapid up and down strokes, but you’re limited to that one point of contact with the strings. Now, with your “pick” still held between your thumb and pointer, take your middle and ring fingers and wiggle them around, flap them in to your palm, imagine using both at the same time to brush upwards on your air guitar, while you’re still strumming and picking with your “pick.” Now, you have three points of contact with the strings, and I’m sure you can picture how much more sound you could pull out of a guitar.

This use of fingerpicks allowed Chris to have more reach with his right hand. He could keep a song propelled forward rhythmically on the low strings with the pick, while playing higher strings with his middle and ring fingers, allowing him to play a melody and rhythm at the same time, in the same way a finger-style guitarist can use their thumb to play a bass line while their fingers pluck the melody but …

… Chris didn’t really do that. He didn’t fingerpick in the classic sense. Some tunes, like “Kick the Stones,” involved some detailed, intricate picking, but most of the time, Chris used his fingerpicks more like weapons-clawing, scraping, and popping strings to great effect. The result is an intense, propulsive, rhythmically complex sound that is immediately identifiable as Chris.

Chris turned in a rendition of 'Hell Hound' that night [Robert Johnson Tribute] that was unforgettable. He was Robert Johnson that night. One man, one guitar, one boot, and he tore it up. As we were leaving, the legendary Robert Lockwood Jr. pulled me aside and asked if I worked for Chris. I replied that I did, to which he said, “Tell that boy he plays like three men.”2

Fingerpick Tricks

Chris had a couple of standard “moves” with the fingerpicks that are pretty unique, if only in the power behind their execution. His playing was controlled chaos, but a few Whitleyisms are identifiable if you watch him enough. I call them the “claw,” the “walk,” and the “pop” - nomenclature you may not find elsewhere.

“The Claw”

It’s a fairly standard Whitley move to use the middle and ring fingers simultaneously in either a kind of “flapping” motion towards the palm to strum upwards, or held rigidly in a claw shape, and using the entire arm to tear upwards at the strings in a rather violent motion. Chris used the claw in both quiet passages and loud ones. Watching him play the verse of “Make the Dirt Stick” is a good example of the Quiet Claw, while “Gasket” is a good example of the Violent Claw. The pick is used for downstrokes, while the fingers are used for upstrokes, generally speaking.

“The Walk”

Another standard move is one I think of as “The Walk.” This one gets a little tricky to describe, but it’s a rapid movement of the ring finger towards the palm, followed quickly by the middle in the same motion, and then immediately followed by a downward strum with the pick.

Go back to your “air guitar” for a second. Snap your ring finger into your palm, followed by your middle (kind of like your fingers are “walking”), and then “strum” downwards with the pick, in a kind of 1-2-3 motion. Now do that as fast as you can. The result, when done relatively slow, is a “Ba-duh-bum” triplet. Chris could do this so fast that it made the notes slur together, so instead of a “ba-duh-bum,” he’d get a “burrrrRUM.” He’d often do this move several times in succession to add rhythmic interest, especially at the end of phrases. “Phone Call” is full of this type of move, with plenty of variations. He also used this to accent certain chords, especially to end songs.

“The Pop”

A third move Chris used all the time is a Pop. This is just using the middle or ring finger to “pop” out a note on a string, almost always the first string. The end of the main riff in “Phone Call” is a great example, but he used this sort of outward pluck frequently, wherever it suited the song to do so. A string-breaking move, for sure.

Chris also tapped the strings with the picks, and even strummed downward with the fingerpicks here and there (although that might be accidental). He also did do a bit of a more standard fingerpicking pattern with them as I mentioned above, songs like “Kick the Stones” exhibit this. He could also “pinch,” or “grip” a string with the middle finger, while also plucking another with the pick.

Flatpick Style

Chris used the regular flatpick (sharp, and with X’s carved in it for grip) for precision work, like fast runs and single notes, and for keeping a steady beat. The sharp point is helpful for precision, and helps the pick stay out of the way of the fingerpicks.

For the most part, Chris used the pick on the lowest three strings for downstrokes, while using the fingerpicks for upstrokes on the highest three. But like anything Whitley, there aren’t any rules and often he’d just seem to use whichever, wherever he wanted, as he played.

He would use the pick to accentuate downbeats, too, in a kind of heavy smash, would use the pick for upstrokes and alternate picking during fast runs, and even strum like any player would use a pick.

None of this is a rigid set of rules, and it’s likely that Chris didn’t even think much about the “hows” and “whys”; he just made the music come out. There are endless variations in his techniques, and often in performance. Every time he’d play a phrase in a song he’d employ a different way to pick it each time through. Chris was constantly improvising within the framework of his songs, even if that improvisation was just using the pick to hit that note instead of the fingerpicks. It’s impossible to nail down exactly how he played many songs because they constantly changed.

All of these factors combined into Chris’s unique picking style. Many of his songs are actually quite simple in chord shapes and melody, and so his ability to add a lot of rhythmic excitement and complexity is a huge factor in what makes his music so intriguing. A brand new guitar student can play the chords in “Dirt Floor,” as beautifully haunting as they are, but without the rhythm behind those simple chords, we’re left with nothing.

So …?

This isn’t meant to be a lesson, or “The Complete Guide to Playing like Whitley” - just observations on technique that I’ve made over years of being quite obsessed with Chris’s picking style. I’ve applied much of that to my own playing, but I’d never say I “play like Chris Whitley” or that I can copy him, as I have no interest in even trying and I’m nowhere near as good a player as he, or many of you reading this, are.

You can certainly play his songs without using his special techniques, and make them sound wonderful that way. Quite a few folks can cover his tunes with just a regular pick or fingerpicking and sound great, which is testament to how great the songs are even when separated from Whitley’s own playing. But I really do hope that anyone reading this who plays guitar will strap on some fingerpicks and give it a shot. Also, I hope any non-players could at least glean a little insight into something that made Chris so special. As Greil Marcus wrote about Chris’ Hellhounds performance at the Robert Johnson Tribute in Fall 1998,

With seven years to live, he looked dead-man skinny in a white T-shirt; a black bowler made him look like Malcolm McDowell in A Clockwork Orange. He shook the strings of his National Steel guitar into an odd, atonal, broken account of Johnson's most resistant composition, and made you believe he understood it from the inside out.3

Jack Ferick in a comment on The Popdose Guide to Chris Whitley (no longer available online).

Ken Helie, CW Tour Manager (see John Mayer's tribute to Chris in which this anecdote appeared.)

Really enjoyed reading this as a fan of Chris' music and as a player who uses different techniques with the right hand. Stranglers hands and Clockwork Orange reference are spot on!

*Great* article. Thank you. Will be re-reading it a lot, I suspect.