We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things not because they are easy, but because they are hard. …. Many years ago the great British explorer George Mallory … was asked why did he want to climb [Mount Everest]. He said, "Because it is there." Well, space is there, and we're going to climb it.

It may seem odd that I open this discussion of Chris Whitley’s guitar sound with excerpts from JFK’s Going-to-the-Moon speech. But, take my word for it, sending a manned space capsule to the moon v. Katie writing about guitars? Similar degree of difficulty …. You know the word “illiterate”? Well, I’m “im-music-ate.”

Fortunately, where JFK had the wizards at NASA to assist him in achieving his moon-shot goal, I have the generous musicians at the All Things Chris Whitley group to help me achieve mine. In fact, they’ve already helped me write about Chris’ guitars in great detail, both electric and acoustic. So, why write about Chris’ guitars? Because they are central to the sound he created. Here, I’ll focus much less on the guitars and much more on the sound Chris made with them.

Instruments of Choice

Whitley had many of the same guitars in his arsenal as most other guitar players: a range of acoustics, from National resonators to Dobro/Regal models to a Gibson E-125 to a Martin 00-15; and a range of electrics, from Fenders to Gibson Les Pauls to a Danelectro. Here I’ll focus briefly on Chris’ Nationals and his out-of-the-ordinary electrics.

National Resonators

Whitley is best-known for playing National resonator guitars. Resonator guitars are designed to amplify sound in much the same way that Thomas Edison accomplished this feat when he invented the no-electricity phonograph. Resonator guitars perform this amplification trick via the aluminum cone(s) housed within the guitar body. It's all about the cones: how many?, how mounted?, etc. Also peculiar to resonator guitars is their dynamic range: the difference between the quietest and the loudest sound an instrument can make. Unlike electric guitars, resonators allow the player to attack the strings in different ways, thereby producing different levels of amplitude. Chris explained why he loves Nationals in this excerpt from In the Foreground:

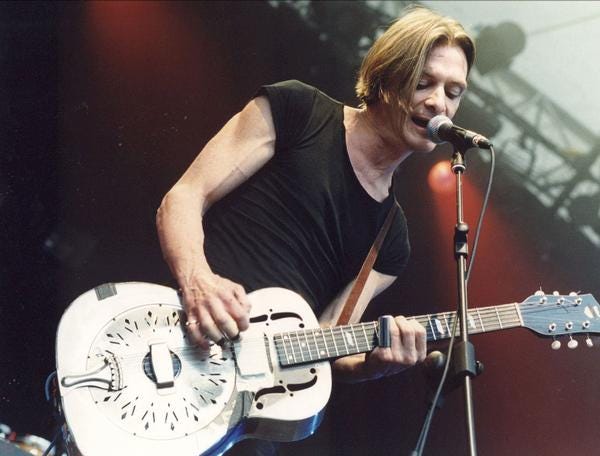

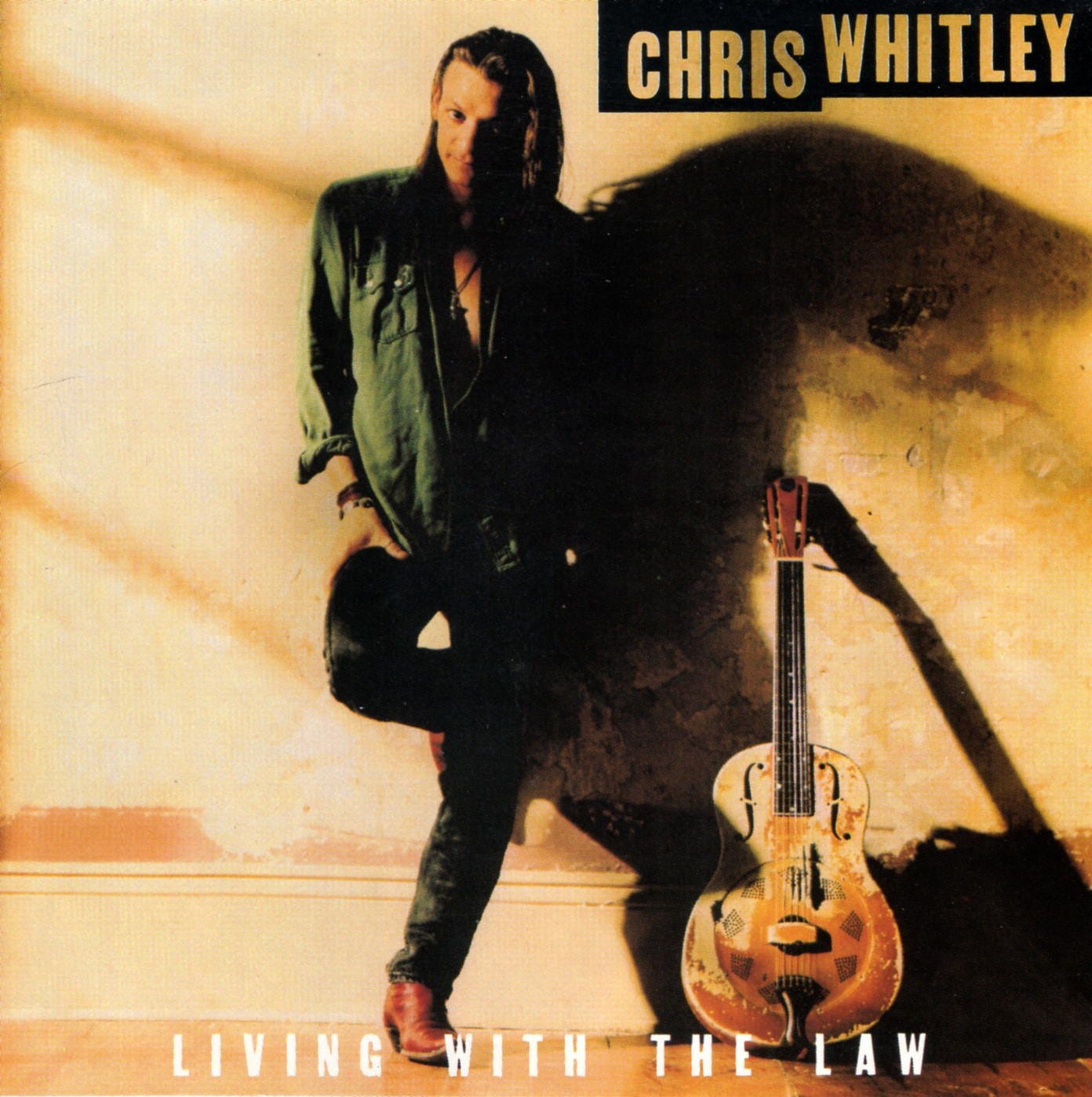

Chris played several Nationals, all single cone: a Triolian, two Style Os, and a Resophonic 1133. His Triolian is iconic, so much so that many refer to it as “the Chris Whitley guitar.” I’ve written in depth about this guitar, which Chris called “Mustard,” and which was featured on the cover of Living with the Law:

Among the other Nationals Chris favored was the Style O, of which he owned two: a vintage National String Instruments 1940 model and, from 2003 on, a new National Resophonic Company model from 2002.

@carltristynfletcher9496 - commenting on an excerpt of Chris’ performance at the Robert Johnson tribute - captures the power of these resonators, especially in Chris’ hands:

The single cone resonator guitar is not really an instrument, it is a mechanical expression of what is in the artist's Soul. It is loud and dangerous and unpredictable. Like anything powerful. That is why it is most suited for the blues, and why it sometimes sounds tragic. It pierces the heart. Like Chris did.

An out-of-the-ordinary acoustic Chris frequently played is the National Resophonic 1133. Why the 1133? I don't know much about guitars and don't have great discernment regarding their different tones [Check out this page for a full discussion by someone who speaks guitar]. One difference between the 1133 and Chris’ other Nationals is that the 1133 ‘vents’ sound not only out of the guitar’s front but also out of its back. Perhaps this accounts for tonal differences that even I can hear between the 1133 and Chris's National 1930/31 Triolian, aka Mustard. Listen to “Indian Summer” played first on the 1133, then on Mustard, and I think you'll understand why Chris included the 1133 in his National guitar collection.

“Indian Summer”" played on the 1133 (Rosebud, 1998-04-14):

“Indian Summer” played on Mustard (CBGB’s, 1998-03-09):

Stand-Out Electrics

Exceptional electrics Chris wielded include the National Resolectric R-1 and two Rick Kelly (Carmine Street Guitars) custom-made beauties (well, until daughter Trixie got her hands on them).

National Resolectric R-1

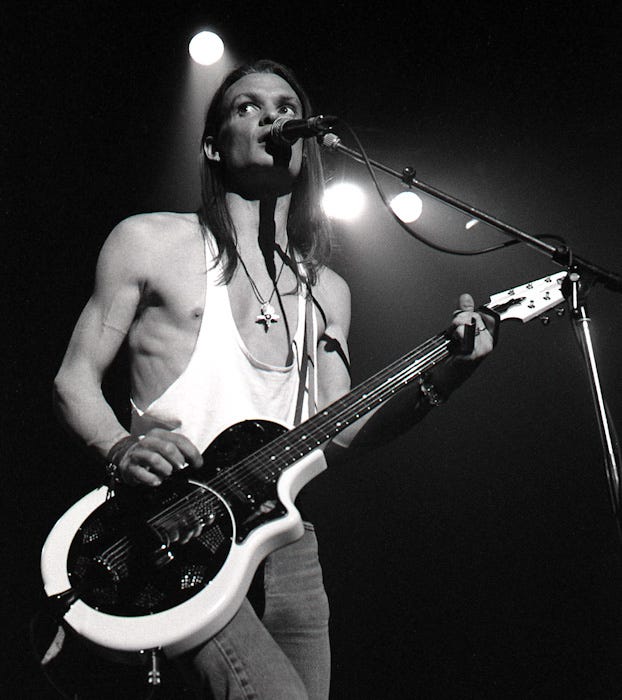

The National Resolectric is a cross between a resonator guitar and an electric guitar, employing an aluminum cone just as National’s other resonators do. This is a solid body instrument designed to be played amplified offering a choice of magnetic or under bridge pickup sounds. The traditional National single cone is set into a single-cutaway solid body with coverplates on both sides - that is, sound vents out of both the front and back of the guitar’s body:

This video captures Chris playing his Resolectric on “Poison Girl” during his tour opening for Tom Petty in 1991.

Kelly Custom Guitars

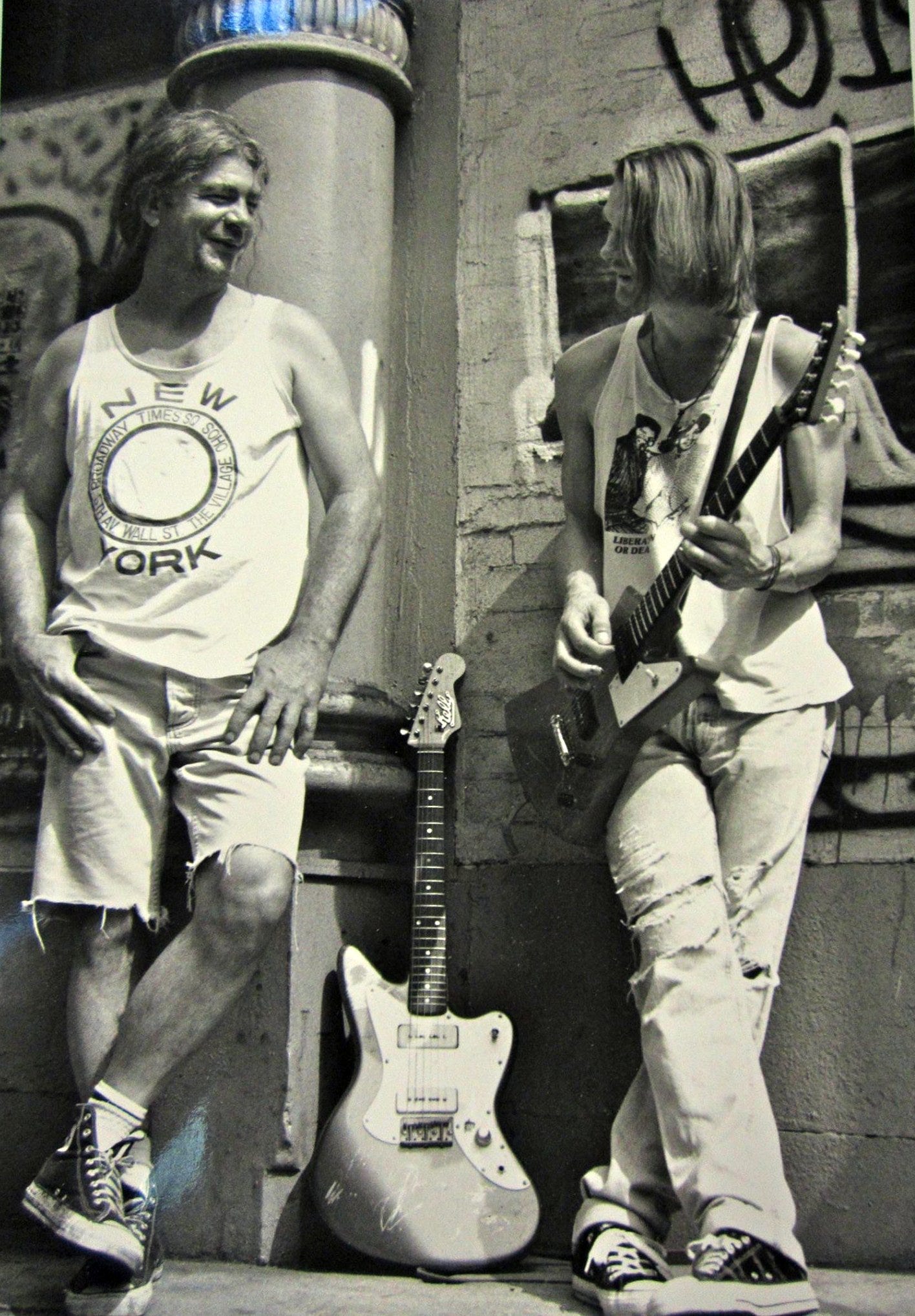

Rick Kelly, owner and luthier of Carmine Street Guitars and a long-time friend since the late 70s, built two custom guitars for Chris: the Kelly Explorer (which Chris is holding in the photo below) and a Jazzmaster-like custom (leaning against the building).

As far as I can tell, the Explorer is mainly distinguished by its futuristic appearance; many other luthiers also make Explorers, e.g., Gibson. Read more about Chris’ custom Explorer on Carmine Street Guitars Instagram. As with the Explorer, the Jazzmaster is also manufactured by many others. The cachet seems to be that both of Chris’ Kellys are custom made by hand.

So … nothing especially unusual about Chris’ choice of guitars; what makes Chris unusual is not the guitars he played but the way he played them. In any event, Chris himself best expressed how different guitars produce different songs:

I write on different guitars and come up with different things on different ones. That’s why I got into using guitars in different tunings to throw myself off. I’m very pragmatic and self-taught. So if I play something like a little Martin acoustic I’ll come up with different things because the Martin’s easier to play. You don’t have to bang on it, it’s not quite so difficult. The chords are a little bit sweeter and it’s a little easier to phrase on. [Dean Budnick, “CW Seeks the Inspiration to Redefine,” Jambands]

Open Tuning and Simple Chords

Although he grew up appreciating the top rock guitarists of the day, Whitley managed to develop a playing style that wasn’t patterned after any of them. He’s come by his rootsy feel more through songwriter instinct than note-for-note study.

“I learned to play guitar from writing songs,” he points out. “My playing has been influenced by the things that I heard growing up, but I make up all my own chords, and there’s rarely solos on my stuff…. If there’s an open break in a song, it’s not a clean solo—it’s almost more like a texture, or a simple slide thing, or a bunch of noise. I think … that Jimmy Page influence was very strong‚ because he was so textural with guitar-playing. It was much more about how the guitar sounded than where the solos were and stuff.” [Steve Newton, "Nomadic Tendencies and Jimmy Page Colour Chris Whitley's Creative Outlook," The Georgia Strait, May 29, 1997]

[Whitley] drags guttural tones from a rusty Dobro tuned so abstractly it could only make sense to him. [Frank De Blase, “Agitating Beauty”, roccitymag.com]

Whitley is known for his open tunings, even though he initially felt “insecure” about them [excerpt from In the Foreground, Track 5]:

As Chris frequently said, he has no musical training, no knowledge of scales and chords, no ability to ‘read’ music, no grounding in music theory. He basically made stuff up or played by ear. So, yes, many of his tunings were unconventional. But, as Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers commented, "[s]ome of the world's coolest music happens when instruments fall into the hands of people who don't know - or don't care - what they're supposed to do with them." Chris Whitley didn't know, nor did he especially care, how he was supposed to play a guitar. As Chris admitted, most of the tunings he used

"I've just made up. They're probably in a book; they could be standard tunings for all I know, but I just came up with them in trying to throw myself off. I started playing in open tunings after I'd been playing guitar for about a year. I was sort of refusing to learn how to play -- I never took any lessons -- and it was a kind of rebellious or insecure thing for me." [JP Rodgers, Rock Troubadours]

The photo below is from Jeff Lang, himself an accomplished musician and long-time friend of Chris - they collaborated on Dislocation Blues, one of Chris’ last albums. The photo provides a list of just a few of Chris’ songs, the tuning for each string, and the guitar used for that song. Chris prepared these lists for his guitar techs so that they’d know how-ta-heck to tune each guitar for each song.

Jeff added the colored dots to ‘group’ the tunings, as he explained to the All Things Chris Whitley group:

Red here is Open A. You'll notice some songs have different pitches, but they're all the same intervals as Open A. In other words, conceptually and in practice they're the same tuning. Light blue is Open E, another common tuning. Green is standard tuning [Jeff interjected in a later comment, “His playing - anything but”]. Yellow is one of Chris' pet tunings that does get used a bit by others (John Fahey for one); again different pitches for some songs but same intervals. Purple is another Chris special: bottom 3 strings like Open A, top three like Open E. [I’ve] not heard anyone else use that combination.

Of course the WAY he used 'em sounded like no one else. [emphasis added]

An ATCW group member asked, “How did he get his head around this from song to song?” Another member replied, “It was already in his head, this was to help mere mortals.” Dougie Bowne, his bandmate on Din of Ecstasy and Terra Incognita, had the best reply: “Practice.” If you’re a guitar player wanting to cover Whitley’s music, you need to know about Hiroshi Suda - the man we call ‘The CW Whisperer.” Hiroshi has devoted hundreds - thousands? - of hours to decoding Chris’ music. You’ll find him quoted whenever I write about Chris’ guitar techniques because no other earthling knows them better than he does. Be sure to check out Hiroshi’s YouTube channel and his Chart of CW Tunings.

But it was not only Chris’ idiosyncratic tuning that made his sound unique; the way he phrased his music, the notes not played, the chord structures he played - all contributed to that uniqueness. Brent Johnson, a blues musician and an ATCW group member, aptly explained what made Chris unique:

A lot of Chris' sound, at least as far as I can tell, came from his note choices, his phrasing, his tunings, the chord voicings that were uniquely his. Nobody played like that before him; you could hear influences, but he had taken those pieces and built something entirely his own. The rest was very much the way he physically interacted with the instrument(s). Those are the elements that remain with the player no matter what instrument they are playing, and those things will give any player a unique sound as opposed to any other.

Responding to Brent’s comment, Lee Roy went further:

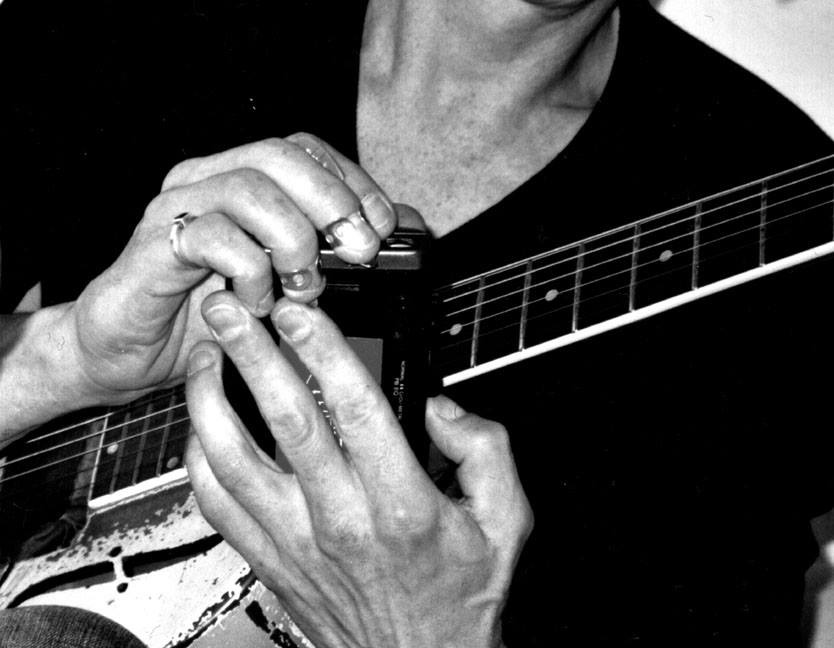

Chris's right hand picking technique, with a flatpick and two fingerpicks [see photo below], was extremely unique and idiosyncratic. Others use that technique, but none like Chris. He quite literally tore at the strings, often quite violently. He could also be pretty intricate, even gentle. I've always wondered why his right hand technique isn't discussed more often, as in my mind it really is THE element that defined his playing.

Most of his chords were simple, they sounded huge because he'd play open strings. A tune like “Dirt Floor,” for example, requires two left hand fingers to play, but without that right hand picking technique, it just doesn't sound correct.

His tunings are mostly fairly standard alternates, there's a few real oddball ones in there, but for the most part he played in regular old open tunings, and used VERY simple chord structures most of the time ... like, really simple. Not trying to denigrate here as that was part of his magic, but his fretting was quite often just two fingers on the same fret, or just one finger. There are exceptions, of course, and he definitely had some tunes with wildly complex structures, but most of his music was constructed from extremely simple chord forms played in combination with open strings. “Scrapyard” is a great example of these simple chord shapes being used to play a lovely melody.

Those simple chords sound ... simple, if all you do is strum them. Chris strummed, plucked, picked, ripped, tore, beat, snapped, punched, scraped, pushed and pulled and created rhythms and patterns that only someone as weird a player as he could--and in my mind, beyond the guitars he played or strings or amps, the reason he sounded the way he did was because of that crazy ass wizard stuff he did with his right hand.1

Notice Chris’ fingerpicks in this close-up of his hands (and their long fingers!) …

… and his slide (custom-made by Ronnie Knight2 - note the winged anvil) and picks.

In summary, Chris Whitley defied categorization by creating his own sound through his choice of instruments, tunings, chords, and attack - the way his hands manipulated guitar strings to express precisely the sound he wanted. David Kahne3 (formerly A&R head at Columbia) said that Chris Whitley is "one of the most talented people I've ever met. He's very much like someone that writes chamber music - he has a perfect idea of every single note." [Tony Scherman, “A Latter-Day Folkie Gets Noisy, NY Times, March 26, 1995]

Elaborating on “every single note,” Stephen McDaid, another accomplished musician and member of the ATCW group, described Chris' music as

“rich in intervallic4 moments which were his own. An interval is the space between notes, and because he had so many ways of tuning his guitars, he could create chords with more colour and texture than 'standard' guitarists. Once he settled on a tuning, it would have been instinct and, no doubt, happy accident that would have made those songs breathe the way they do, and still give us shivers 20-odd years later.”

Ronnie’s day job is working with NASA on projects such as the James Webb Space Telescope, so custom-making a slide was probably as easy as 1 - 2 - 3 ….

Mr. Kahne also engineered and produced Chris’ contribution - “Starve to Death” - to the So I Married an Axe Murderer soundtrack; he is listed as an engineer on Chris’ Long Way Around - An Anthology 1991 - 2001 because he recorded some of the demos included on that compilation.

‘Intervallic’ relates to intervals, which are the difference in pitch between two sounds.

I really, really enjoyed this post. Thank you for putting it together.